Blind spots around Large Goods Vehicles (LGVs) have long been identified as a potentially significant contributor to the cause of serious collisions involving pedestrians and cyclists.

Plotting drivers’ sight lines is often an important aspect of investigations into collisions between vehicles and these vulnerable road users. Such assessments are carried out in order to determine whether one party could have been visible to the other, had they been looking in a particular direction at a given moment.

Common collisions

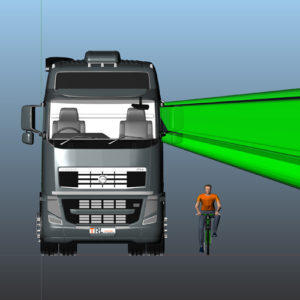

The most common scenarios for LGVs in collision with cyclists and pedestrians are when a truck is moving off from rest or turning left. TRL undertook a visibility assessment which identified that the areas of greatest risk extend across the full width of the front of the LGV and 5 metres down the nearside of the vehicle from the front.

Direct vision assessment

An analysis that seeks to represent the exact vision available to a particular driver can be flawed. Incident drivers are rarely available for visibility assessments, especially if the assessment is carried out at a live accident scene, whilst the driver is being interviewed by the police elsewhere or receiving medical help. In these cases, investigators rely on a ‘stand-in’ colleague, of a similar height to the driver, to plot their visibility. As this traditional method is accepted as not being 100% accurate, TRL undertook a study to quantify what, if any, error is introduced into line of sight measurements when different height drivers are used. The objective was to calculate a percentage error to be applied as a confidence range to subsequent LGV assessments.

Does size really matter?

Best practice

Best practice

Best practice is to always use the incident driver for a visibility assessment. If the driver cannot be available to participate in an assessment, it may be possible to measure their eye point within the vehicle or with respect to other definable points and then use a movable arm and laser pointer method to plot their vision. This may be more accurate than plotting the vision of a ‘stand-in driver’. Although the area of vision and vehicle outline can be measured in two dimensions with a theodolite, a 3D laser scanner will provide a more accurate assessment, as well as allowing modelling which can be presented as images which are more readily understandable to Courts.

A common sense approach should be used; if an object is nearly completely visible, based on a generic assessment, it is probably true that the object will be at least partly visible if the limit of vision is moved. If a conclusion is to be drawn that an object was available to be seen, but the incident driver has not been available for the investigation, it may be necessary to ‘test’ the modelling. This can be achieved by moving the line of ground visibility closer to and further away from the vehicle, redrawing the visibility plane, and checking whether the conclusion still stands. It is likely that this approach would also assist in accounting for the unknowable variables such as seat height movement. Download the full report